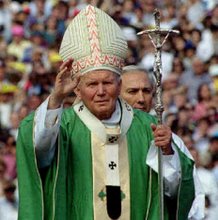

In this chapter John Paul II gives a simple presentation of historical political systems and in which he particularly analyses democracy.

First, he describes the three forms of political organisation (from the perspective of who has power). In a Monarchy power resides in an individual, in an Aristocracy power resides in a social group, and in a Democracy power resides in the whole of society. Each of these systems is valid so long as the purpose of exercising power is to serve the common good, that fundamental moral norms are respected, and that civic virtues are actually exercised. If this is not the case, then Monarchy (and Aristocracy) degenerates into Tyranny, and Democracy into Ochlocracy (domination by the populace).

Democracy, understood not simply as a political system, but also as an attitude of mind and a principle of conduct, does not, in practice, allow for the direct exercise of power by the whole of society; power resides in representatives of the people who are designated by free election.

Catholic social morality favours Democracy because it corresponds more closely to the rational and social nature of man.

Democracy comes into being through a 'state of law', in which social life is established by parliaments with legislative power, and is regulated by law. Thus, Democracy is able to form free citizens who jointly pursue the common good.

Now the Divine Law also comes into play for man, this was given through Moses and is binding, even on those who do not accept Revelation, as natural law. The Decalogue (the Ten Commandments), or natural law, is foundational for any human legislation, precisely because they seek the fundamental good of personal and social life. If any of these commandments is placed in doubt, both human society and man's moral existence is put at risk. This is because law rests not upon human judgement, but upon the truth of being, the truth of God, of man, of all reality.