History shows us many examples of how the prevailing culture has tried to mould the Church according to its own agenda. For instance, in the 1970s at Nowa Huta near Krakow, the Communist authorities tried to build a new city without any religious provision. But the Church there, led by her archbishop, took part in a Mass every Sunday there in an open field.

It is different when the agenda comes from within the Church. I use to the term ‘ecclesiocracy’ in a different way today, not so much as an ecclesial presence guiding society, but as an ecclesial presence shaping the Church according to its own agenda. And where an ‘ecclesiocrat’ is someone who has his or her own agenda for the Church.

We see ecclesiocrats at work in the nurturing of theological positions, understood as projects which stand alongside or even claim precedence over the Teaching of the Church. We feel the presence of ecclesiocrats when the Teaching of the Church is simply set aside to make way for whatever project is on the table.

Where did this tendency, in our era, come from? I would be glad of some input here so I can better make sense of the situation that we are in today. So, please comment on this in order to help me.

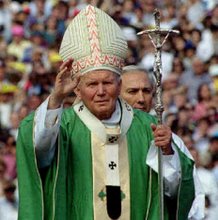

The Church has an agenda, its own. That agenda is not a formula, but a person, as both St John Paul II and Benedict XVI pointed out. The Church’s ‘agenda’, her plan, was given by the Lord in the Great Commission. Any agenda that is given subsequently to the Church, or even searched for, makes the Church look as though she doesn’t have an adequate agenda already.

Ecclesiocrats come in both clerical and lay form. I think that we are so used to them being around today that we hardly notice them, and we become accustomed to the distance that is created between us and the Lord by this human posturing. But we should notice them and take stock because the Church is the Lord’s. It is not ours to shape and mould as we see fit. And we need to be aware of being shaped and styled as ecclesiocrats ourselves.

So, how has ‘ecclesiocracy’ arisen in our day? I am reminded of a letter which Archbishop Heenan wrote to Evelyn Waugh in August 1964 in which he said,

“I think that the leaders of the new thought (if that is not too strong a word) are not so much the young pops as the Catholic ‘intellectuals’ That is what they call themselves and believe themselves to be. Everyone with two A-levels is now an intellectual.” These words suggest the birth of lay ecclesiocrats at the time of the Second Vatican Council. This movement grew apace and became well represented by certain religious interest journals that persist today, and the lay groups which thrive on such religious interest.

Of course, the activity of clerical ecclesiocrats within the Council has been written about extensively, and I don’t intend to go into that here. The theological currents were themselves caused most probably by a deeper anthropological movement. And the theological movement is being given in depth treatment today by some excellent minds.

Clerical ecclesiocrats are, I imagine, more influential/dangerous than their lay compatriots. No doubt they have always been around. But what has produced them today? I ask this because ‘ecclesiocracy’ seems rife in much of the Church today, as though the nature and meaning of the Church and the Christian life is up for total reappraisal!

A realisation can to me when, five years ago, I read Sherry Weddell’s book ‘Forming Intentional Disciples’. As I put the book down, I thought to myself, today priests have become administrators and people have become consumers. But priests need to become pastors again, and people need to become disciples. Our consumerist culture has had a much deeper impact than, I think, any of us is aware of.

Clerical careerism is most certainly a cause of deflecting a pastor into another mode. The National Pastoral Congress of 1980 in Liverpool was another. This Congress had an unspoken question at its root – what kind of a Church would we like today? This is the question of ‘consumer Catholicism’ and, although the 1980 Congress seemed to go nowhere, its underlying agenda became very active in the Church in this country.

Pope John Paul II set out the unchanging ‘agenda’ of the Church in his 2001 Letter, Tertio Millennio Ineunte, detailing in Part 3 the priorities of the Christian life. As proponents of the new evangelisation, Paul VI through to Francis, have straightforwardly re-presented evangelisation in its proper place in the life and mission of the Church, namely, at the forefront. In this way they have addressed a ‘losing sight’ of something that is essentially part of the Church. Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI were notable for embracing new movements which were giving to expression to the Church’s timeless ‘agenda’ and allowing them to flourish. But where do the other agendas belong, and where are they going?