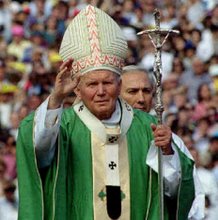

In this cahpter, the Holy Father looks at Europe through the prism of Christianity which, as we will see, is also the root of today's Europe.

The evangelisation of Europe began with a mysterious call which St Paul received, to cross from Asia to Europe and preach the Gospel there (Acts 16: 9). Within a few hundred years Ireland, the western most part of the continent, had become itself a missionary centre of the faith.

Building upon the fabric of the ancient world, it was evangelisation which formed Europe; the Faith favouring the formation of different cultures, different nations, but all linked to the common patrimony of the Gospel. However, it is only with the advent of the Modern Era, when the known world was extended to Asia, the Americas, to Africa and Australia, that Europe was seen in a more objective way.

St Paul's address at the Areopagus in Athens (Acts 17: 22-31) holds the key for what would take place in the wider Europe. In this speech St Paul first recognises the religion of the ancient world and, in so doing, prepares his hearers for a proclamation of the Incarnation and the Redemption. The Church would go on to achieve a profound integration of faith and culture in the peoples of Europe.

The first great 'wounding' of Europe was the 'Great Schism' of 1054 when the Eastern and Western Churches ceased to function together. Then, at the beginning of the Modern Era disputes arose with the Protestant reformation, and the Western Church suffered further divisions.

During the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries - the era of the Enlightenment - Christ began to be rejected in Europe. The Enlightenment was not an outright rejection of God, but an attempt to exclude Christ from thought and from Europe's history.

Today a cultural drama continues for those who reject Christ; for the ideas of these secularists are, in fact, profoundly rooted in Christianity, so deeply has the Gospel marked Europe.

Christ himself gives us a Theology of the Incarnation and Redemption. In the metaphore of the Vine and the branches (John 15: 5ff), Christ shows how God cares for and cultivates his creature. He grafts it onto the stock of the divinity of His Son. From the beginning man has been called into existence in God's image and likeness. By agreeing to be grafted onto Christ, man can fully become himself. By refusing this grafting man is condemning himself to an incomplete humanity.

So, in the European Enlightenment man has endeavoured to cut himself off from the Vine, and thereby he opened up the path that would lead to the devastating experience of evil in the Twentieth century.

According to St Thomas Aquinas evil is the absence of good. For man to deprive himself of the good of being a part of the Vine is to deprive himself of that fullness which God intends for man.

(The above photo I took a few years ago in the churchyard in the village of Birstall in North Yorkshire. It is the gravestone of the late Christopher Dawson, the Catholic sociologist whose life's work was given over to helping Europe rebuild itself on the foundations of the Gospel after the Second World War.)

No comments:

Post a Comment