Europe has never been united by a

material culture, but only by a moral and spiritual one. Christianity, which

had united Europe, haunted the Eighteenth Century, suggesting that a new union

was at hand. Yet the Industrial Era did not achieve what Christianity once had

done. There was now no common conception of reality that could unite people

and, while physical science progressed, philosophy lost its foothold.

The world, seen as a closed, material

order, left no room for moral values or spiritual forces. Nonetheless, this environment

gave rise to semi-theological Deism; that beyond the physical mechanism of the

Universe there existed the Divine engineer.

Although a conflict existed between

science and religion, the opposition between science and philosophy was

greater. The mechanistic hypothesis is more easily reconcilable with faith,

than it is with metaphysical system. Deism broke down precisely because of its

religious and philosophical weakness, and as it did so the mechanistic

hypothesis entered into every aspect of existence – man became part of the

machine. Morality and spirituality were excluded, and humanitarian ideals were

excluded from ordinary life. Science lost its optimism. If everything is a part

of an eternal cosmic process, then everything, including human beings, must

ultimately remain the same.

Luther’s notion that the human person redeemed by grace was merely ‘a

manure heap covered with snow’, had entered deeply into the human psyche.

The ancient doctrine of an eternal

cycle was once again part of philosophy, but now it postulated the gradual

running down of the process to an absolute end. Science could never accept this

repugnant world view, but instead sought to provide new justification for the

theory of an eternal process. Yet the only progress that it could conceive of

was the progress to an eternal death. Moreover, without a God metaphysics – the

mathematics behind material substance – is vapid. Science is nothing more than

the measurement of the material world; science cannot explain the cause of

things. Even so, the more that the parameters of science became delineated, the

more pressing became the need for metaphysics.

You can see in this history of the Enlightenment the various human

movements by which man wrestled with his lot, exploring within, seeking without,

struggling with his condition, in any way except the relationship of grace that

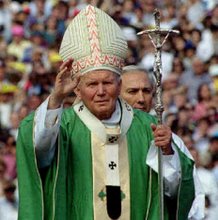

was his proper call. The New Evangelisation is thus the way of calling to man

in his desperate and anxious search, and helping him to trust again in grace and not

in his own resourcefulness.

Science cannot replace philosophy, nor

can it act as a religion, nor can it unite societies. Science is an

intellectual technique, not a moral system. If you know how to use it, then it

can become a tool for you. Good science has been led by a humanitarian spirit,

a spirit which has been born of science but of religion.

If the Eighteenth Century could manage

without dogmatic religion, could the Twentieth Century manage without

Liberalism?

No comments:

Post a Comment