I have just finished reading

George Weigel’s new book Evangelical

Catholicism, and can now make some comments about it. First of all, can I

say that I have long since thought of George Weigel as one of the few true

journalists who are around to day, and therefore, as someone who is especially

worth reading, if not following. A journalist is someone who is able to look at

a state of affairs, see it’s relationship to truth, and then communicate an

accessible understanding of that state of affairs to the ordinary person; you

and me. George Weigel has this gift; many who call themselves journalists do not.

Journalism involves knowledge and truth, it involves analysis and synthesis,

but above all, it is a God-given art. We need journalists.

Evangelical Catholicism is an extraordinary book because it begins to see and

propose something which most of us have not even considered: what the Church of

the New Evangelisation will look like. We

have heard about the New Evangelisation and have some appreciation of what it

is, and why it is here, but we have not perhaps thought about its effect upon

the Church itself. The Church of the New Evangelisation is not a ‘new’ or

‘changed’ Church, but is the Church whose culture has been deeply effected,

transformed, by the influence of the historical event which is the start of a

new era of evangelisation. Evangelical Catholicism is the expression which

describes the renewed culture of the Church as the people of the Church, newly

and unaffectedly, extend their friendship with Christ to the peoples of the

world today.

The expression “evangelical

Catholicism” is itself new to our ears, as was the expression “new

evangelisation”. When I was at seminary, the divide in the Church was between

conservatives and liberals. This divide subtly mutated to one between

non-conformists and conformists. This situation was very fluid and for at least

a decade the polarity in the Church has been evangelical/institutional. The

institutional pole of the Church is marked by two currents: cultural

Catholicism and neo-Pelagianism. The evangelical current in the Church is

marked by a focus on the person of Jesus Christ and grace, and a docility to the

Magisterium. As Weigel says in his book, “You are a Catholic because you have

met the Lord Jesus Christ and entered into mature friendship with Him – which

is to say, in evangelically Catholic language, that the sacramental grace of

your Baptism, should you have been baptised as an infant, has been made

manifest in the pattern of your life as your have grown into human maturity.”

(p34-35)

As I read Part 1 of the book,

which speaks of the nature of evangelical Catholicism, I felt a certain

resonance with how I have come to understand the New Evangelisation. I couldn’t

understand however, why Weigel introduced the word ‘evangelism’; ‘evangelism’

is not the same as ‘evangelisation’. It was Part 2 of the book however, which

really opened a new leaf for me. In Part 2 Weigel speaks about the concrete

reform of the different ‘sectors’ of the Church and, in doing so, begins to

show how the New Evangelisation needs the renewal of the interior culture of

the institutional Church, and what that renewed institution will look like.

So, for instance, the reform

of the Episcopate (something which is especially pertinent in our own context), when seen in the context of the New Evangelisation, is not

simply something which will help the Church manage itself better, but is

something which is essential to the very nature of the Church. What the Church

today needs, says Weigel, is “twenty-first century apostles, [to lead] the Catholic

Church out of the shallows of institutional maintenance and into mission amid

the cultural whitewater of postmodernity”. (p122) The emphasis that Weigel goes

on to lay on the reform of the Priesthood, Liturgy, Consecrated Life, and the

Lay vocation, amongst others, reveals how the New Evangelisation needs a

renewed Church, renewed in its structures and, above all, in its interior

culture. What stands in the way of the New Evangelisation is not the “whitewater

of postmodernity”, but is a Church which is not configured to Christ.

Weigel does a great service

to the Church with Evangelical Catholicism in showing that the reform of the

Church “is not a matter of good management practice, but so that its essential

structures support the universal call to holiness and the universal call to

mission.” (p259) I recommend this book to you for some deep reading and

reflection.

I was a little intrigued by

some of those whose help in writing the book Weigel acknowledges. He cites both

a University Faculty in Argentina and the Argentinian Bishop’s Conference. Now,

although Weigel had written the book by July 2012, I wonder just how much his

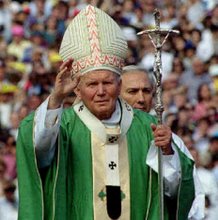

ideas might have been shaped and shared by a certain Argentinian prelate. And whatever influence this book might have in

the Church, the Holy Father seems already to be on the brink of leading the

Church through to that place where She needs to be.

.jpg)