This is the last of the posts of Fr Fleming's visit, and it is apt that the theme should therefore be end of life, rather than beginning of life. After the John Paul II Evangelium Vitae lecture on Thursday evening, Fr Richard and myself were treated to the second half of the double bill, along with about 20 priests from the Archdiocese of Birmingham, to Fr Fleming's talk on 'End of Life Decision Making: Priestly Pastoral Care and Responsibility' on Friday, at a clergy information day put on by SPUC at the Paragon Hotel in Birmingham.

Fr Fleming started by noting that, at one time, one could take it for granted that doctors and priests had the same objective - to care for the whole person. However, a parting of the ways has happened, in a similar way that there has been a parting of the ways between faith and culture, such that for many doctors care is directed only at the physical self, in an almost mechanical sense. Worse still, for many health service bureaucrats, medicine has become a service, with customers, and has been reduced to an element of the market economy, governed by cost effectiveness. But we are dealing with 'patients' (those who suffer) and not 'customers' (pawns in a consumer society).

The first quality which governs decision making in end of life care is 'beneficence' - that is, the need to do good rather than evil. At its most basic level, this means primum non nocere (not to do the patient any harm), but it should also include acting for the good of the patient, and in its more radical forms, benevolent self-effacement (which includes some personal cost) and even heroic sacrifice (like those doctors who have stayed behind in epidemics to treat the sick and have fallen foul of disease themselves, or Damian the Leper, the priest who cared for lepers in a colony and caught the disease himself). The second quality is compassion. This is the virtue of being willing to act once one realises what is the right thing to do. Very often we are presented with cases in the media of people who want to kill themselves, and we are called to be compassionate to their plight. True compassion can only act in accordance with what is morally right, and never be what is morally wrong dressed up as compassion. Compassion does not release us from moral responsibility, and is not a quick fix.

The first aim of medicine is to cure. In end of life situations, though, medicine is dealing with care not cure. Compassion is the first virtue that is required in this circumstance. It follows that there must be adequate nursing care, the assurance that the person is not going to be abandoned in their pain, and the requirement of competence (being incompetent is effectively not caring). In these ways doctors and priests share in the priestly ministry. They care on the basis of need not right. They are not 'service deliverers'; they are not caring because of a contractual duty, but based upon trust.

The flagship of those who support such things as euthanasia is 'autonomy', the right to free choice and self-determination. We are not, however, free to choose what is morally wrong. Sickness clouds over our own self-image and so reduces the ability to act autonomously. Claims that very sick people are competent to make these life and death decisions has to be questioned simply from the point of view of their own competence to view the matter clearly. The right to life has to be above all autonomy, as it is the fundamental moral principle. Often when a sick person is saying to their relatives 'It would be better if I were to die', they are not looking for a way out but an assurance that their relatives will be there. The worst thing is for the family to stand there and say 'Yes you ought to die'. Studies in Australia reveal that in a hospice a small percentage of those with terminal illness (around 10 per cent) wished to be killed. But once they were assured that they would not be alone, and they would not suffer unnecessary pain, that number dropped to zero. Often the call for euthanasia is based on our inability to watch suffering. It's more a case of "Please put grandma out of my misery."

The major principle for us must be the inherent dignity of human life, no matter how frail, how vulnerable or how damaged. Once we surrender this profound respect for human life in some hard cases, it is just a matter of where you draw the line, and who draws it and why. And on what do we then base those decisions? Where do we draw the line? Do we judge it on cost? On our disgust? On our whim? On our convenience?

Eugenics is nothing new. It was around long before Hitler. He just picked up on what was already there in literature. The so-called archetypal English gentleman, Bertrand Russell, wrote: "Feeble-minded women, as everyone knows, are apt to have enormous numbers of illegitimate children, all, as a rule, wholly worthless to the community. These women would themselves be happier if they were sterilised, since it is not from any philoprogenitive impulse that they become pregnant" (Marriage and Morals, London 1972, p.130). There are others like James Lachs who wrote that "the only way to treat hydrocephalic children 'humanely' is to 'mercifully' put them to death". And Mary Anne Warren advocated "the kind, quick, painless, and direct method of lethal injection." Notice how they use the language of compassion in order to justify direct killing. More insidious still, in pre-Nazi Germany, was the opinion of Karl Binding that "we are spending lots of time, patience and care on the survival of life devoid of value."

In response contemporary secular bioethics is driven by the rejection of suffering as an unredeemable evil. It follows that in order to get rid of the suffering one should get rid of the person. The Church however continues to promote the inherent dignity of the human individual. For the Church, the definitive suffering is the loss of eternal life, being rejected by God - damnation. Of this definitive suffering modern day followers of the Enlightenment project have no account.

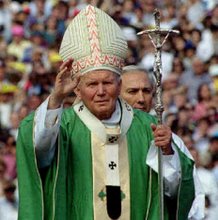

Pope John Paul II is the great witness to hope and antidote to the desire to eradicate visible suffering. Nietzsche wrote that "the doctor should give to the sick each day a fresh dose of disgust." Pope John Paul II disgusted many commentators in the secular media by publicly living out his life to the end, not hiding his frailty and disability. Even though his activities were curtailed, he made the most of the life he had until the very end. He practised what he preached in relation to his duty of care of his own life.

When we look at those most cruel forms of euthanasia - the killing of those in a persistent vegetative state - we see the lie of 'mercy killing'. Indeed the very name 'persistent vegetative state' objectivises and dehumanises the person. We should, rather, call them the 'permanently unconscious'. Under the Mental Capacity Act, and indeed taken from the Bland case judgement, it is now legal in this country to kill those who are permanently unconscious by withdrawing feeding after one year of unconsciousness. This is a most cruel thing to do, as it makes the person starve to death and dehydrate. The thing is the media often present such people who are permanently unconscious as near to death anyway. But nothing could be further from the truth. They are far from death. In fact, that is the problem for the health care bureaucrats. They simply WON'T die, unless killed by withdrawing basic care. The law gets around it by stating that feeding is medical care. Certainly the insertion of a feeding tube is a minor medical procedure, but thereafter it is only the administration of food. When we have lunch it is not a medical procedure. It is something necessary for our self-preservation. So when we feed the incapacitated we are feeding - a corporal act of mercy - someone too vulnerable to feed themselves.

The words of Pope John Paul II resonate especially: "I feel the duty to reaffirm strongly that the intrinsic value and personal dignity of every human being do not change, no matter what the concrete circumstances of his or her life. A man, even if seriously ill or disabled in the exercise of his highest functions, is and always will be a man, and he will never become a 'vegetable' or an 'animal'". It is therefore the duty of all who have care of those who are incapacitated to respect this dignity in every way: "Medical doctors and health-care personnel, society and the Church have moral duties toward these persons from which they cannot exempt themselves without lessening the demands both of professional ethics and human and Christian solidarity." This solidarity calls for us to be there for the sick and dying and to act on their behalf when they are robbed of their voice and cannot respond. It follows that "the sick person in a vegetative state, awaiting recovery or a natural end, still has the right to b asic health care (nutrition, hydration, cleanliness, warmth, etc), and to the prevention of complications related to his confinement to bed." In other words, a right to basic nursing care. "I should like particularly to underline how the administration of water and food, even when provided by artificial means, always represents a natural means of preserving life, not a medical act. Its use, furthermore, should be considered, in principle, ordinary and proportionate, and as such morally obligatory, insofar as and until it is seen to have attained its proper finality, which in the present case consists in providing nourishment to the patient and alleviation of his suffering."

asic health care (nutrition, hydration, cleanliness, warmth, etc), and to the prevention of complications related to his confinement to bed." In other words, a right to basic nursing care. "I should like particularly to underline how the administration of water and food, even when provided by artificial means, always represents a natural means of preserving life, not a medical act. Its use, furthermore, should be considered, in principle, ordinary and proportionate, and as such morally obligatory, insofar as and until it is seen to have attained its proper finality, which in the present case consists in providing nourishment to the patient and alleviation of his suffering."

"The evaluation of probabilities, founded on waning hopes for recovery when the vegetative state is prolonged beyond a year, cannot ethically justify the cessation or interruption of minimal care for the patient, including nutrition and hydration. Death by starvation or dehydration is, in fact, the only possible outcome as a result of their withdrawal. In this sense it ends up becoming, if done knowingly and willingly, true and proper euthanasia by omission."

I really have to thank SPUC for bringing Fr Fleming to Birmingham once again, so that we could hear his clear reasoning and be guided by his teaching. If you have the opportunity to hear him speak then take it.

Fr Fleming started by noting that, at one time, one could take it for granted that doctors and priests had the same objective - to care for the whole person. However, a parting of the ways has happened, in a similar way that there has been a parting of the ways between faith and culture, such that for many doctors care is directed only at the physical self, in an almost mechanical sense. Worse still, for many health service bureaucrats, medicine has become a service, with customers, and has been reduced to an element of the market economy, governed by cost effectiveness. But we are dealing with 'patients' (those who suffer) and not 'customers' (pawns in a consumer society).

The first quality which governs decision making in end of life care is 'beneficence' - that is, the need to do good rather than evil. At its most basic level, this means primum non nocere (not to do the patient any harm), but it should also include acting for the good of the patient, and in its more radical forms, benevolent self-effacement (which includes some personal cost) and even heroic sacrifice (like those doctors who have stayed behind in epidemics to treat the sick and have fallen foul of disease themselves, or Damian the Leper, the priest who cared for lepers in a colony and caught the disease himself). The second quality is compassion. This is the virtue of being willing to act once one realises what is the right thing to do. Very often we are presented with cases in the media of people who want to kill themselves, and we are called to be compassionate to their plight. True compassion can only act in accordance with what is morally right, and never be what is morally wrong dressed up as compassion. Compassion does not release us from moral responsibility, and is not a quick fix.

The first aim of medicine is to cure. In end of life situations, though, medicine is dealing with care not cure. Compassion is the first virtue that is required in this circumstance. It follows that there must be adequate nursing care, the assurance that the person is not going to be abandoned in their pain, and the requirement of competence (being incompetent is effectively not caring). In these ways doctors and priests share in the priestly ministry. They care on the basis of need not right. They are not 'service deliverers'; they are not caring because of a contractual duty, but based upon trust.

The flagship of those who support such things as euthanasia is 'autonomy', the right to free choice and self-determination. We are not, however, free to choose what is morally wrong. Sickness clouds over our own self-image and so reduces the ability to act autonomously. Claims that very sick people are competent to make these life and death decisions has to be questioned simply from the point of view of their own competence to view the matter clearly. The right to life has to be above all autonomy, as it is the fundamental moral principle. Often when a sick person is saying to their relatives 'It would be better if I were to die', they are not looking for a way out but an assurance that their relatives will be there. The worst thing is for the family to stand there and say 'Yes you ought to die'. Studies in Australia reveal that in a hospice a small percentage of those with terminal illness (around 10 per cent) wished to be killed. But once they were assured that they would not be alone, and they would not suffer unnecessary pain, that number dropped to zero. Often the call for euthanasia is based on our inability to watch suffering. It's more a case of "Please put grandma out of my misery."

The major principle for us must be the inherent dignity of human life, no matter how frail, how vulnerable or how damaged. Once we surrender this profound respect for human life in some hard cases, it is just a matter of where you draw the line, and who draws it and why. And on what do we then base those decisions? Where do we draw the line? Do we judge it on cost? On our disgust? On our whim? On our convenience?

Eugenics is nothing new. It was around long before Hitler. He just picked up on what was already there in literature. The so-called archetypal English gentleman, Bertrand Russell, wrote: "Feeble-minded women, as everyone knows, are apt to have enormous numbers of illegitimate children, all, as a rule, wholly worthless to the community. These women would themselves be happier if they were sterilised, since it is not from any philoprogenitive impulse that they become pregnant" (Marriage and Morals, London 1972, p.130). There are others like James Lachs who wrote that "the only way to treat hydrocephalic children 'humanely' is to 'mercifully' put them to death". And Mary Anne Warren advocated "the kind, quick, painless, and direct method of lethal injection." Notice how they use the language of compassion in order to justify direct killing. More insidious still, in pre-Nazi Germany, was the opinion of Karl Binding that "we are spending lots of time, patience and care on the survival of life devoid of value."

In response contemporary secular bioethics is driven by the rejection of suffering as an unredeemable evil. It follows that in order to get rid of the suffering one should get rid of the person. The Church however continues to promote the inherent dignity of the human individual. For the Church, the definitive suffering is the loss of eternal life, being rejected by God - damnation. Of this definitive suffering modern day followers of the Enlightenment project have no account.

Pope John Paul II is the great witness to hope and antidote to the desire to eradicate visible suffering. Nietzsche wrote that "the doctor should give to the sick each day a fresh dose of disgust." Pope John Paul II disgusted many commentators in the secular media by publicly living out his life to the end, not hiding his frailty and disability. Even though his activities were curtailed, he made the most of the life he had until the very end. He practised what he preached in relation to his duty of care of his own life.

When we look at those most cruel forms of euthanasia - the killing of those in a persistent vegetative state - we see the lie of 'mercy killing'. Indeed the very name 'persistent vegetative state' objectivises and dehumanises the person. We should, rather, call them the 'permanently unconscious'. Under the Mental Capacity Act, and indeed taken from the Bland case judgement, it is now legal in this country to kill those who are permanently unconscious by withdrawing feeding after one year of unconsciousness. This is a most cruel thing to do, as it makes the person starve to death and dehydrate. The thing is the media often present such people who are permanently unconscious as near to death anyway. But nothing could be further from the truth. They are far from death. In fact, that is the problem for the health care bureaucrats. They simply WON'T die, unless killed by withdrawing basic care. The law gets around it by stating that feeding is medical care. Certainly the insertion of a feeding tube is a minor medical procedure, but thereafter it is only the administration of food. When we have lunch it is not a medical procedure. It is something necessary for our self-preservation. So when we feed the incapacitated we are feeding - a corporal act of mercy - someone too vulnerable to feed themselves.

The words of Pope John Paul II resonate especially: "I feel the duty to reaffirm strongly that the intrinsic value and personal dignity of every human being do not change, no matter what the concrete circumstances of his or her life. A man, even if seriously ill or disabled in the exercise of his highest functions, is and always will be a man, and he will never become a 'vegetable' or an 'animal'". It is therefore the duty of all who have care of those who are incapacitated to respect this dignity in every way: "Medical doctors and health-care personnel, society and the Church have moral duties toward these persons from which they cannot exempt themselves without lessening the demands both of professional ethics and human and Christian solidarity." This solidarity calls for us to be there for the sick and dying and to act on their behalf when they are robbed of their voice and cannot respond. It follows that "the sick person in a vegetative state, awaiting recovery or a natural end, still has the right to b

asic health care (nutrition, hydration, cleanliness, warmth, etc), and to the prevention of complications related to his confinement to bed." In other words, a right to basic nursing care. "I should like particularly to underline how the administration of water and food, even when provided by artificial means, always represents a natural means of preserving life, not a medical act. Its use, furthermore, should be considered, in principle, ordinary and proportionate, and as such morally obligatory, insofar as and until it is seen to have attained its proper finality, which in the present case consists in providing nourishment to the patient and alleviation of his suffering."

asic health care (nutrition, hydration, cleanliness, warmth, etc), and to the prevention of complications related to his confinement to bed." In other words, a right to basic nursing care. "I should like particularly to underline how the administration of water and food, even when provided by artificial means, always represents a natural means of preserving life, not a medical act. Its use, furthermore, should be considered, in principle, ordinary and proportionate, and as such morally obligatory, insofar as and until it is seen to have attained its proper finality, which in the present case consists in providing nourishment to the patient and alleviation of his suffering." "The evaluation of probabilities, founded on waning hopes for recovery when the vegetative state is prolonged beyond a year, cannot ethically justify the cessation or interruption of minimal care for the patient, including nutrition and hydration. Death by starvation or dehydration is, in fact, the only possible outcome as a result of their withdrawal. In this sense it ends up becoming, if done knowingly and willingly, true and proper euthanasia by omission."

I really have to thank SPUC for bringing Fr Fleming to Birmingham once again, so that we could hear his clear reasoning and be guided by his teaching. If you have the opportunity to hear him speak then take it.

2 comments:

I'm sorry but i can't understand why this blog is not THE no 1 Catholic Blog!

The astounding photography & depth of discussion are amazing.

Those who missed Fr Fleming's lecture missed out, but at least Fr Julian was able to give an excellent description.

The theme of 'sffering' touched on & explained through the suffering of Pope John 2, is imperative. It seems much of the developed world does its utmost to deny the existence of suffering, & if it does exist we must rid ourselves of it quickly..eg suicide, euthanasia...This is a very dangerous thing, since if a person is severely clinically depressed, those 2 options seem most plausable. I know this since i have experienced this kind of thinking in 2 major depressions.

That's why we need pro-life medics & Catholic teaching on the value of suffering...to keep us alive. Ipersonally was comforted by the bravery of our previous Holy Father..& how he picked up his cross, united it to Christ, & carried it.

I pray we all can do the same..because like it or not suffering comes to us all in some shape or form.

Sorry, if i digress..but i wanted Fr Julian to know that the information posted on his blog can touch people in a personal way for the good..

God bless,

Jackie

Thanks also to Fr Richard...who i don't know but enjoy his posts!

God bless,

Post a Comment