This post completes my notes on the second part of Dawson's book "Progress and Religion". In the New Year I will post giving some final comments on the text and, hopefully, listing in summary the basic elements and factors that Dawson speaks of.

The major religions can indeed be

criticised today. Intellectual absolutism, a focus on the metaphysical, and a

preoccupation with the Eternal, have all tended to turn men’s minds away from

the material world and to devalue natural knowledge. Today’s culture wants a

religion which leads to social action and development.

Whether or not we set Christianity

aside today in favour of the new movement of evolutionary vitalism, what is

present in our culture is firstly, moral idealism. This is the fruit of an age

of religious faith and spiritual discipline. Secondly, humanitarianism. This is

the fruit of a society that has worshipped the Incarnation – the Divine

humanity of Jesus Christ. But if dogmatic Christianity is rejected, this

humanitarianism will be divorced from its foundation, and it will not then

continue to exist in the same way.

A created, non-organic religion will be

neither truly religious nor completely rational, and so it will fail. The West

then, has two choices; either to abandon Christianity, and with it faith in

progress and humanity, or embrace anew moral idealism and humanitarianism.

Whichever takes place the religious impulse needs to be expressed openly and

not in furtive ways. Yes, it is true that a religion without Revelation is

still attractive, but this is also a religion without history. But one of the

great characteristics of Christianity is that it is historical, and is not

merely an unprogressive metaphysic, as in Eastern religions. Nor is Christianity

purely rational. The discursive reason is arid ground for a dynamic religion;

metaphysics is necessary if reason and religion are to meet. On the other hand,

the religious impulse finds rich soil in historical reality. All religions,

even Oriental ones, need something of this. In Christianity, the historical

element is identified with the transcendent and gives humanity its value.

Christianity is, in fact, the Religion of Progress. What flows out of Christianity

is not an abstract idea, but spiritual values in history. With Christianity

something new has entered into history and has created a new order of creative,

spiritual progress. This is not grasped by Reason, a faculty which organises

the past, but is grasped by Faith, which is the promise of the future.

Christianity is also the source of that

movement which genuinely nurtures humanity. A real humanitarianism needs the

support of a positive religious tradition. The desire for a just social order, which

was once the vision of classical Liberalism (whose root is a religious impulse),

will diminish if it is not reinforced by spiritual conviction. In the past

society was given moral force by Christianity, enabling it to grapple with and

dominate its circumstances. Science does not have that influence; it cannot

organize and transform human existence alone. It needs a moral purpose to drive

it.

Oriental religions tend to deny the

importance of the material world, and thus support the view that religion is

incompatible with science. Christianity is different; it does not see the material

world as evil. It does not reject nature, but rather, seeks its ennoblement.

The way in which Western science and law has organized nature is not alien to

Christianity, but is analogous to the progressive spiritualization of human

nature by Christianity. The future of humanity depends upon the harmony and

co-ordination of these two processes.

Today, the West is absorbed in the task

of material organization, to the detriment of moral and spiritual unity. Yet,

these two elements – science and religion – have given Europe its distinctive

character.

Without religion, society becomes a

neutral force – for aimless material activity – which can tend towards either,

militarism or economic exploitation, or towards serving humanity in a genuine

way.

Without science, society becomes

immobile and unprogressive.

Europe has never possessed the natural

unity of the other great cultures. A spiritual foundation, rather than a

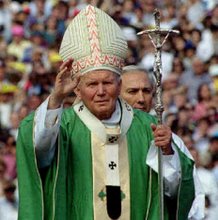

political one, was the uniting factor. And in being that foundation we see that the Church

was a much nobler institution than the State.

Today, we take it for granted that it

is materialism that unifies society, and that religion is a source of division.

However, the marginalization of religion has led to the impoverishment of our

culture. The state of society today is an anomaly and is not the normal condition

of humanity.

Culture is essentially a spiritual

community, which transcends economic and political orders. The genuine organ of

culture is the Church, not the State.

The Church is the embodiment of a

spiritual tradition, resting not upon a material power (the State), but on the

free adhesion of the individual. In the past, the Church co-existed with

multiple States, without absorbing or being absorbed by them. This co-existence

enabled both material independence and political freedom, and it gave rise to

the wider unity of our civilization. This process of spiritual integration is

the true goal of human progress.